Pictures submitted by Wayne Ault

ault26.jpg

<-- Back |

Home |

| Rescue At Sea

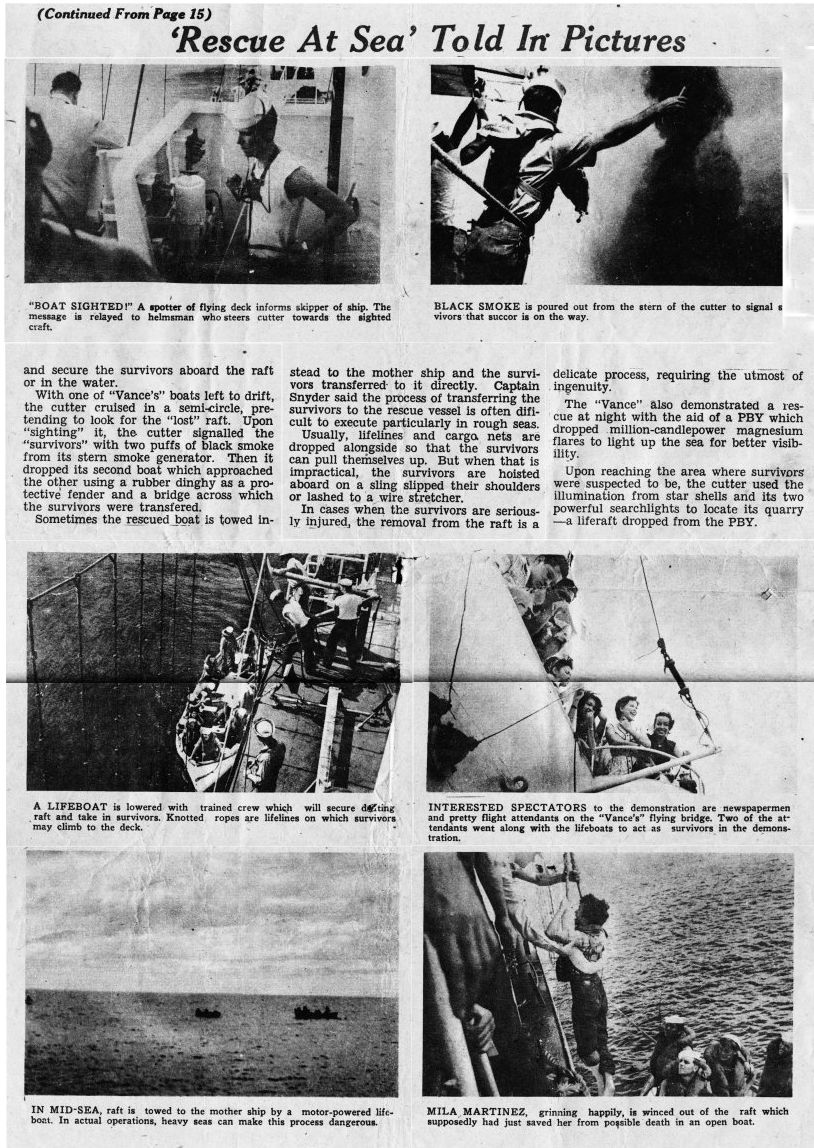

Coast Guard Demonstrates Latest Techniques Of Saving Lives In Maritime Disasters By Eduardo Lachica Philippine shipping and aviation will be emboldened to know that when disaster strikes the United States Coast Guard will be working as far as it is humanly possible to save lives. The new USCG Search and Rescue Command at Sangley Point was set up for this purpose late last year. Its main objective is to safeguard military operations but official quarters have stressed that the group would regard almost as equally important the protection of civilian airplanes and ships in the event of accidents and adverse weather conditions. The Coast Guard has made rescue work its proven specialty. Its far-flung duties range from patrolling the iceberg-infested arctic seas to picking up downed airmen in combat zones. The Sangley Point rescue center is one of six similar centers in the Pacific area. Actually, it would depend a lot upon the assistance of the US 13th Air Force which has an air-sea rescue unit of its own, but it would serve as the pivot for rescue operations in Philippine waters. The science of survival has been perfected to a point where a shipwreck or a well-executed ditching no longer carries the dreadful connotations of slow death at sea. A man with a regulation Mae West can float like a cork, fight off sharks and live on rain water for days; the modern liferaft with built-in-radio, sail, water pouches and fish hooks gives survivors more than a fighting chance of seeing home again. The Coast Guard and its allied services have developed various methods which uncannily pinpoint the location of survivors in the middle of the sea. A week ago, the Coast Guard invited a number of Civil Aeronautics Administration and Philippine Air Lines personnel and newsmen to see just how these methods work. The observers were taken aboard the USCG cutter "Vance" which will serve as the mainstay of the Search and Rescue Command. A sleek, 1460-ton one-stacker, the "Vance" was recently de-mothballed and taken by its skipper Commander Gerald T. Applegate for a four-months tour of duty in the Pacific. Waiting aboard the "Vance" was one of the ablest rescue director in the Coast Guard. He was Captain William H. Snyder, USCG,the man in charge of the Sangley Point rescue center. The captain carefully explained every detail of the coordinated rescue demonstration which the "Vance" staged that afternoon and evening. Put out to sea 10 miles southwest of Corregidor island , the "Vance" went through its paces with clock-work precision. Two boats were lowered, one of take the part of a drifting raft from a ditched aircraft or a sunken liner and the other to act as the rescuing boat. The Coast Guardmen enacted four cases in which the rescue boat was to approach and secure the survivors aboard the raft or in the water. With one of "Vance's" boats left to drift, the cutter cruised in a semi-circle, pretending to look for the "lost" raft. Upon "sighting" it, the cutter signaled the "survivors" with two puffs of black smoke from its stern smoke generator. Then it dropped its second boat which approached the other using a rubber dinghy as a protective fender and a bridge across which the survivors were transferred. Sometimes the rescued boat is towed instead to the mother ship and the survivors transferred to it directly. Captain Snyder said the process of transferring the survivors to the rescue vessel is often difficult to execute particularly in rough seas. Usually, lifelines and cargo nets are dropped alongside so that the survivors can pull themselves up. But when that is impractical, the survivors are hoisted aboard on a sling slipped their shoulders or lashed to a wire stretcher. In cases when the survivors are seriously injured, the removal from the raft is a delicate process, requiring the utmost of ingenuity. The "Vance" also demonstrated a rescue at night with the aid of a PBY which dropped million-candlepower magnesium flares to light up the sea for better visibility. Upon reaching the area where survivors were suspected to be, the cutter used the illumination from star shells and its two powerful searchlights to locate its quarry − a liferaft dropped from the PBY. |